Researchers have made a breakthrough in the field of personalised medicine by growing functioning human heart tissue carrying an inherited cardiovascular disease.

The advance comes as the result of a collaborative effort between scientists from the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Boston Children's Hospital, the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and Harvard Medical School.

Scientists modelled the cardiovascular disease Barth syndrome, a rare X-linked cardiac disorder caused by mutation of a single gene called Tafazzin, or TAZ.

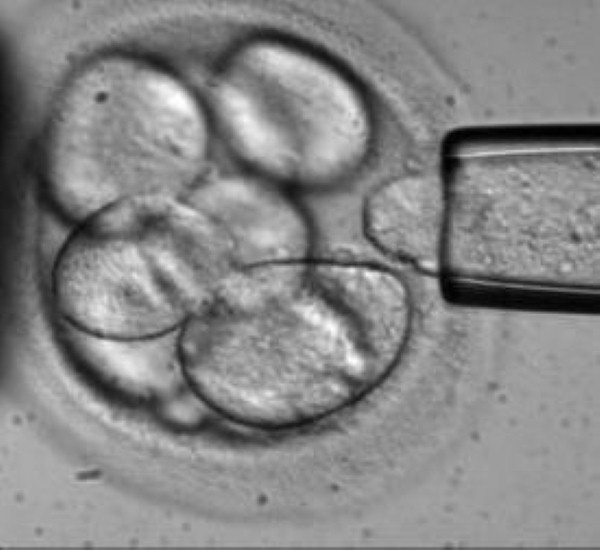

Skin cells were taken from two Barth patients; these were manipulated to become stem cells that carried the patients' TAZ mutations.

Rather than being used to generate single heart cells in a dish, the cells were tricked into joining together in the way they would if they were forming a diseased human heart. This was achieved by growing them on chips lined with human extracellular matrix proteins that mimic their natural environment.

The tissue thus created contracted very weakly, as would the heart muscle seen in Barth syndrome patients.

Genome editing was then used to mutate TAZ in normal cells, confirming that this mutation is sufficient to cause weak contraction in the engineered tissue.

"You don't really understand the meaning of a single cell's genetic mutation until you build a huge chunk of organ and see how it functions or doesn't function," said Dr Kevin Parker.

"In the case of the cells grown out of patients with Barth syndrome, we saw much weaker contractions and irregular tissue assembly."

The scientists also found that the TAZ mutation works in such a way to disrupt the normal activity of mitochondria, which produce energy – although the overall energy supply of the cells appeared to be unaffected by the mutation.

They describe a direct link between mitochondrial function and a heart cell's ability to build itself in a way that allows it to contract – a newly identified function for mitochondria.

Barth syndrome cells produce an excess amount of reactive oxygen species or ROS as a result of the TAZ mutation. In the laboratory, quenching ROS production restores contractile function, but the scientists have yet to ascertain whether this could be replicated in human or animal models.